↵ NEWS

One Of The Last New Argonauts

A Review of the ARGUS II Artificial Retinal Implant By Ross A. Doerr

Released: 1/19/2023

Author: Ross A. Doerr, Top Tech Tidbits Reader

Share to Facebook

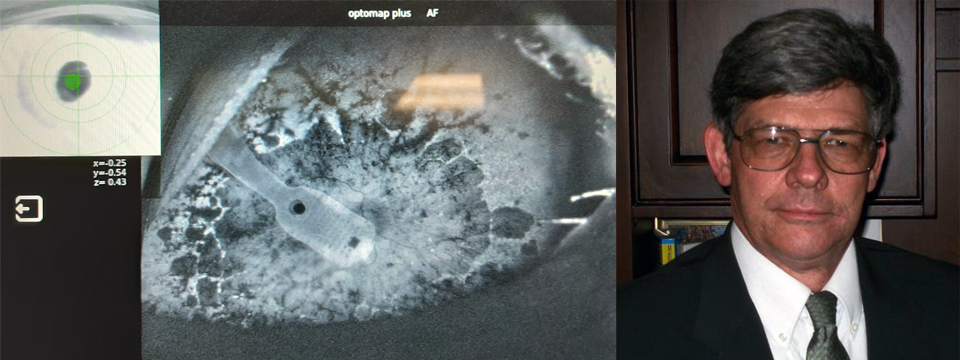

Photo: Photo of Ross A. Doerr next to an x-ray photograph of the ARGUS II Artificial Retinal Implant tacked onto his retina.

Alternative Article Formats: This review is approximately 45 pages long as a Word Document. If you would prefer to read it in Microsoft Word format you can download it for easy offline reading here. If you prefer PDF format, you can launch and save an accessible PDF version of this very same document here.

Just like the online version below, each document includes a Table of Contents on the very first page with jump links to each chapter. Click on any Chapter heading to return to the Table of Contents. This article and all of the information within it are the sole property of Ross A. Doerr. Top Tech Tidbits reproduces this content with the sole permission of this author.

Argus

In Greek mythology, Argus was the builder and eponym of the ship Argo, and consequently one of the Argonauts. It was said he constructed the ship under Athena's guidance. Argus is also credited with creating a wooden statue of Hera that was a cult object in Tiryns.

A second and perhaps as well-known reference of the name comes from Homer's "the Odyssey." There, Argos is Odysseus' faithful dog who, upon the return of Odysseus, recognizes his master, howls once in recognition then dies. After twenty years struggling to get home to Ithaca, Odysseus finally arrives at his homeland. In his absence, reckless suitors have taken over his house in hopes of marrying his wife Penelope.

A third and perhaps less known reference to the name is Argus Panoptes, or simply "Argos," a hundred-eyed giant in Greek mythology. He was the son of Arestor, whose name "Panoptes" meant "the all-seeing one".

"You see things; and you say, "Why?" But I dream things that never were; and I say, "Why not?"

- George B. Shaw and Robert F. Kennedy

Table of Contents

Chapter 1: Put an artificial what in my eye?

Chapter 2: To get one, or not to get one? That is the question.

Chapter 3: Implant Surgery

Chapter 4: What turns me on?

Chapter 5: Pushing The Envelope

Chapter 6: Side Effects

Chapter 7: Change Can Turn Hope Into Reality

Epilogue

Author Biography

Chapter 1: Put an artificial what in my eye?

"Opportunity knocks. It does not kick the door in."

This short book describes how I found out about an artificial retina for treating blindness, learned what it is and what it is supposed to do. I will describe why I decided to undergo the surgery and have it implanted in my right eye.

If this medical procedure is successful, it would restore some of my vision. I'm sure that many of you have never heard of an artificial retina and, like me, have no idea what one is. That's exactly how I was when I first heard about it.

What is an artificial retina and how does it work?

First, this particular artificial Retina is called an "ARGUS II," and it is manufactured by Second Sight Medical Products in Sylmar, California. To me, a biomedical prosthetic which is essentially a glorified computer chip being manufactured in California wasn't surprising. Where else would something like that be developed?

I will try to describe it in understandable terms. I had to read through the online description of it a few times before I had a good grasp of it. This artificial retina is a tiny electrode array with 60 electrodes protruding from the bottom that is surgically implanted directly onto the retina of the eye. The electrodes are pressed down into the retina and held in place by a surgical tack. An Antenna in the form of a wire about the thickness of a human hair, comes through the wall of the eyeball, wraps around the eyeball and connects to the artificial retina. This is how the implant wirelessly receives the signal from a "Visual Processing Unit" (VPU) that is worn on the patient's belt.

I wear a pair of glasses with a camera mounted on them connected by a thin cable to the (VPU). The camera images are processed into light images that are sent to a coil mounted on the bow of the glasses. That coil wirelessly transmits the signals to the artificial retina, and the 60 electrodes then send that signal to the brain through the optic nerve to the visual cortex. You with me so far?

What kind of vision would I have, assuming the implant surgery is successful?

I am told that I will have a field of vision that is roughly 20% of what a regular sighted person has, and it will not be "normal" vision. It will be digitally reproduced. This also means no peripheral vision. To see something off to my right I need to turn my head in that direction so the camera can pick up what's there. The way it was described to me is that the visual field is like looking through a screen the size of a 3"x5" index card held out at arm's length. In retrospect, that description is a very accurate one. Do you have all of that? Any questions? Well, when I first heard about this, I sure had questions. The foregoing is a very short explanation of the electrode and is now quite obsolete.

To be clear, I began writing this in June, 2019, two months after my ARGUS II artificial retina was implanted. A more detailed description of the entire process is explained later.

The Artificial Retina was implanted on the retina of my right eye on April 19, 2019 and it works great.

The process of how I arrived at this point dates back two years to a visit with my regular eye doctor here in Maine. I would not have gone to see her had my eyes not started to itch. If you aren't blind or are someone with a visual impairment of some sort, that last sentence may be lost on you.

I've been blind for well over thirty years. Like many other blind people, I'd simply stopped going to eye doctors a long time ago for the very logical reason that "I've heard it all before." When you go to an eye doctor, they tell you that you're blind, a statement of the obvious, followed by a variation of the "There's no cure for your kind of blindness," another statement of the obvious, followed by the ever-hopeful, "…but researchers are making advances all the time, so don't lose hope."

Those of us who are blind tuck statements like those away in the same memory register with all election year campaign promises. I'm not being cynical; I'm just being realistic.

This is exactly why many of us blind and visually impaired people simply stop going to eye doctors. To a lot of us, myself included, it's simply a waste of time and money. The exception to that rule is if you ever need a form signed by a doctor to qualify for some sort of governmental benefit, or if something happens to bother one or both of your eyes, like an annoying itch.

The latter is what drove me to see my eye doctor. Both of my eyes had begun to itch pretty badly, and I wanted to see if there was something that could be done to make the itching stop. My eye doctor told me that I had developed a rather sizable cataract in each eye and that's why my eyes were itching. While she does not do cataract surgery, she could refer me to a team of surgeons who are local and perform cataract surgery. Since Medicare and my supplemental health insurance covers the procedure, I agreed to speak with the surgeons. Making a very long story short, I had the cataract surgery performed on my left eye on November 6, 2017, followed by the same surgery on the right eye on November 20. The surgery on my left eye went without a hitch. The same cannot be said for my right eye. Problems developed almost at once. Apparently, a chip of cataract in the eye had been missed by the surgeon. The doctor tried to dissolve it with eye drops without success, so another surgery was done on May 4, 2018 to get the last bit of cataract out.

This is where the "Fairy Godmother" department stepped into the picture. One of those cataract surgeons is the father of the surgeon in Boston who performs the artificial retina implant procedure at the New England Eye Center. This surgery is not available in either Maine or New Hampshire. Boston is the closest place to have it done. The cataract doctor here in Maine asked if I might be interested in talking to his son about it.

Not wanting to rush into anything so invasive without doing some research, I spent a lot of time online, reading about the artificial retina and listening to YouTube videos about how recipients of the ARGUS II implants feel about it, and then agreed to speak with the doctor at the New England Eye Center. One important thing to mention here is that insurance would cover it.

There are two very important considerations to note about all of this. First, we live in Maine. Boston is, to state the obvious, two states away. If you don't live in New England, that may not seem important to you, but it's an important consideration when you have to keep medical appointments in Boston during winter months and you live in Augusta, Maine. Just to drive from Augusta to the Maine/New Hampshire border takes two hours and through five or six different weather zones. In the winter, that's an important consideration when only one of us can drive a car. Boston is three hours away, one way in light traffic. This is proof positive that my wife is a saint.

Then there is the all-important insurance coverage. What we learned when we started making trips to Boston is that, while some Maine-based insurers will cover a doctor's appointment for a "consultation" down there, the same is not necessarily true for surgical procedures done by that same doctor in the same place where the insurance company paid for the consultation. Insurance companies definitely live in a world of their own.

I learned a lot from speaking with the surgeon about the procedure. First, the cornea of my right eye, the tentative "target eye" for the ARGUS II artificial retina, was at that time, too cloudy for him to see the retina clear enough to give me a solid opinion whether I was a good candidate for the procedure. The second cataract surgery didn't get the errant cataract chip after all, and the eye was not only still cloudy, but its cornea was damaged and developing painful blisters. This, so far as the surgeon and a potential implant was concerned, moved everything back to "square one" until the cornea was clear enough for him to be able to see the retina.

He did tell me, however, that I may be a good candidate for the procedure because I used to be able to see (a prerequisite for the surgery at the time), and that my optic nerve seemed to still be intact (also a prerequisite at the time). My blindness, according to my medical records, is due to Retinitis Pigmentosa and Macular Degeneration. Therefore, the underlying optic nerve should be intact and functional, and that's what the artificial retina needs in order to operate.

But first, the cloudy cornea needed to be dealt with. This meant I needed a partial cornea replacement. Upon hearing this, I wasn't pleased that my right eye, already abused at the hands of modern eye surgery twice in seven months needed yet another surgical procedure. Since I'd already been exposed to the New England Eye Center, a truly impressive facility, I agreed to see a cornea surgeon to have the cornea replacement done there.

The partial cornea replacement surgery was done on October 16, 2018 at Boston Eye Surgery and Laser Center. It was done with no complications and I can't say enough good about them. By January 10, 2019, all of the sutures had been removed from my eye with no complications, signifying a successful procedure.

I had a follow up appointment with Dr. Andre Witkin, the artificial retina surgeon in March, 2019. He could see the retina clearly and pronounced me a good candidate to have the ARGUS II artificial retina implanted. All of this was after another complete eye exam, including photographs of the inside of my eye. I can say without doubt that the New England Eye Center is extremely professional and thorough in everything necessary to determine eligibility for a cutting-edge surgical procedure.

Dr. Witkin then asked me if I'd like to have the procedure done. This is where I learned how thin the line is between that all-important "informed consent" between a doctor and patient, and "too much information." Dr. Witkin took all of the time necessary to describe exactly what was going to be done, how it was going to be done and how the procedures involving the scleral band (the bit that gets wrapped around the outside of the eyeball connecting to the electrode array inside the eye) have changed to be a lot safer. He went into very graphic detail about absolutely everything. I remember asking my wife, also sitting in the room with me and listening to all this, was doing. Her response was something like: "A bit weak in the knees."

I happen to have a bit of a medical background. Part of it comes from my work in the Medicaid Benefits field where I worked for many years and part of it from my far distant past when I could still see, as an emergency medical technician. I understood enough of his description to ask what was to me the most important question of all. "Doctor, I will be under a general anesthetic during all of this? Completely out cold, right?" The answer was yes. Thank God. I agreed to the procedure and it was promptly scheduled for April 19, 2019.

The point I hope anyone reading this will take away from it all, is this — if there is an opportunity to get some sort of treatment for your eye condition, it doesn't hurt to listen to a doctor. Let the doctor tell you about it, then investigate it on your own. Admittedly that's easier said than done, especially if you are blind. There is also just plain luck that can and often does figure into something like this.

For the record, and this is only my opinion, there will always be someone out there to proclaim that there is no such thing as luck. They are just plain wrong. Think about it.

How often have you heard about someone who, on a hunch, purchased the winning lottery ticket? Or that person who changed their mind about something only to learn later that he or she averted disaster because of that change? What about the person who gave up his place in line to someone who ended up being the 1,000th customer at a business and won a fabulous prize? That person's luck was good, and the person who'd given up his or her place in line ended up being the one with the bad luck that day. There are countless examples of good and bad luck out there. So yes, there really is such a thing as luck, but luck requires you to do something to get it. Only rarely will it jump into your lap and start licking your face.

Chapter 2: To get one, or not to get one? That is the question.

"If you obsess over whether you are making the right decision, you are basically assuming that the universe will reward you for one thing and punish you for another."

"The universe has no fixed agenda. Once you make any decision, it works around that decision. There is no right or wrong, only a series of possibilities that shift with each thought, feeling, and action that you experience."

- Deepak Chopra

How do I decide?

Before I agreed to have the ARGUS II retinal prosthetic implanted in my eye, I first needed to make the psychological "yes" or "no" decision about the idea of having an implant inside my eye to treat my blindness. That process was neither simple nor quick. To try to simplify something complicated, a decision like this one has two very basic components: the decision whether or not to have the surgery done, and insurance coverage. Both are extremely important for obvious reasons.

For me, the first part of this decision was to do the necessary research in an effort to separate the advertising surrounding the artificial retina from the reality. Believe me, I spent a lot of time on the website for Second Sight Medical Products, checking into this artificial retina implant. I also reached out to the world wide web for reading material and read anything and everything I could find about it. It is a retinal prosthetic that has been implanted into blind people all over the world. If you ever decide to look into this sort of surgically implanted medical prosthetic, be prepared to find YouTube videos about it in German, Spanish, French and several other languages. In the final analysis, the ARGUS II is exactly what I described in Chapter I, a glorified computer chip with 60 electrodes sticking out of its bottom side which, once implanted onto the patient's retina, promises to restore some level of artificial eyesight.

Will research help my decision?

If you research this type of prosthetic online, and there are more than one of them out there, you'll find countless videos featuring a recipient of the ARGUS implant when it's "activated" for the first time. Suddenly that person "sees" something. It's all very persuasively produced. It was all too convincing. It came across to me as advertising, and I have a healthy aversion to that sort of promotion. (Full disclosure here, I subsequently agreed to let Second Sight video me for the purpose of producing that exact type of YouTube video.)

So, I mentally shifted from what I viewed as advertising, to researching any medical papers, goals and reports about the ARGUS II Implant. Then I tried to separate everything I'd read into some semblance of "reality" for me to digest. So, just how do I determine "reality" for something like this anyway?

If you aren't blind or visually impaired, you may find it hard to understand this type of healthy skepticism and how the decision-making process for a blind person differs from the way a sighted person might decide to do something of a similar nature. Many blind folks approach this type of decision from a very, very different background. Let me try to explain how "our" decision making processes differs from a sighted person's approach.

As a blind person, how do I cope?

It all stretches back to our respective life experiences, how we grew up with blindness and what our experiences have been over time; as well as how we have dealt with experts, rehab types and the medical profession. For me, looking back, I've undergone a very full spectrum of personal feelings that have been generated by the opinions and philosophies of all types of so-called "experts" in blindness.

Going through life, there are the helpful rehabilitation types who are generally unable to get past the phrase, "You need to accept your disability." My biggest disability has always been the inability of others to either accept blindness or see me as a normal man who just happens to be blind. If you're blind you'll see the difference there.

Then there's the goal of the rehabilitation industry to make us "independent." That's not a term that has much of a definition when you're blind. It means something very different to sighted people than it does to the blind.

Once you understand that the rehab industry more or less defines "independence" as the blind person achieving the least amount of dependency on others that he or she can engineer in their circumstances, they can safely get off a rehab counselors' caseload. That's the goal, after all. In the final analysis, it's all on the blind person.

Blindness restricts you more than other people in modern society, and that's the reality. Once you become a blind adult, your general goal is to achieve the life triad that everyone else strives to have: a job with benefits paying a decent wage, decent housing and transportation. A paying job is at the peak of that triad. If you have a good enough job, you can afford the housing and transportation you need. You know, just like people who can see. That's basic independence for blind adults.

The foregoing leaves a few other important, defining things, out. First, the blind get left behind in life at a fairly early age and we know it. We don't get drivers licenses or the same socialization exposure that our sighted counterparts do. It also results in us developing a very different set of values and we evaluate priorities based upon those values, not on how others may think. Simply stated, not only do we have to live life differently than sighted people, but we also have to make decisions differently.

Another set of experiences in our background that give us a different outlook on life is the religious approach to living. Religion is important to almost everyone, in one way or another. Which religion you are really doesn't matter, as long as you are satisfied with it. There have been many very well-meaning religious people in my life who insisted that, if I would just accept Jesus as my savior, my eyesight would be restored. Really! Sadly, since I'm still blind, it's evidence to them that I haven't accepted him. Don't they realize that they're blaming me for being blind? Then there was the other branch of religion that insists that my eyesight would be restored if I'd learn whatever it is that God is trying to teach me. If I'd just do that, my eyesight would be restored. There it is again, the implication that my blindness is my fault.

Of course, neither of these groups seemed to be able to tell me how I'm supposed to actually do things their way so that I can get my eyesight back. They do however, insist that it's for me alone to figure out because God works in mysterious ways. Again, since I can't seem to figure out what God wants, I guess I'm going to stay blind.

This reminds me of a quotation I jotted down out of a Stephen King book long ago. It reads: "The beauty of religious mania is that it has the power to explain everything. Once God (or Satan) is accepted as the first cause of everything which happens in the mortal world, nothing is left to chance or change. Once such incantatory phrases as 'We see now through a glass darkly' and 'Mysterious are the ways he chooses his wonders to perform' are mastered, logic can be happily tossed out the window."

If you're not blind, how often have you had that kind of "God" rationale leveled at you? Those of us who are blind get this sort of thing a lot. My point is that life experiences like these temper how we see things and how we make decisions.

Next there's the spiritual groups. They will tell me that my blindness is a direct result of me not having learned the lesson in "this life" which has been carried over from my "past life" because I "refuse" to learn it. Once again, my blindness seems to be all my fault.

All of this spiritual stuff was followed by a woman I heard on late night talk radio a few months back insisting that all disabilities are a direct result of our inability to master our emotions. Now, my blindness is a result of not mastering my emotions? Where do these people get this crap?

The point I'm trying to make here is that those of us who are blind, or who have any other type of disability for that matter, seem to attract these well-meaning folks, and they seem to be around constantly for some of us more than others.

After a few decades of that stuff, it starts to impact the decision-making process.

So, well you may ask, what do I happen to believe?

From the religious/spiritual perspective I believe this: "The holy man said, had God meant man to fly he'd have given him wings. The Scientist said that God gave man the intelligence to make his own wings. And the Adventurer said "I have wings. Show me the way."

So, why am I telling you this?

There is one other thing that you may or may not find yourself exposed to if you tell others you're considering getting this type of implant. I'm talking about the crowd of conspiracy theorists out there. The ARGUS II is an artificial retina made by Second Sight Medical products in Sylmar California. It is not experimental technology derived from an alien space craft that crashed somewhere. It is also not part of a top-secret government project being run by some faceless, super-secret government scientists monitoring us by computer from a dimly illuminated lair in the basement of the Pentagon. It's a medical advancement folks. That's all.

Getting back to my personal brand of decision making, I acknowledge much of the foregoing baggage as being a large part of my background. It resurfaces from time to time, kind of like a nasty bout of constipation. I've learned to keep all of it in perspective and it doesn't require any Ex-lax.

I was unlucky enough to be born with this visual condition and I'm blind. I've been lucky enough to have this opportunity to regain some of my vision if I agree to have the procedure done. I'm intelligent enough to do the research and to "see it" through a lens of reality. I'm also old and experienced enough in real world life to understand that decisions like this one can lead me into a disappointment trap. By that I mean: disappointment exists in that place between expectation and reality. Over the years, I've learned to temper my expectations as much as possible. But wow, the chance to see something again?

I hope that I can be more realistic than someone I met a very long time ago. Way, way back when my parents were taking me from doctor to doctor to try to find a cure for my impending blindness, I met another young boy in my same situation. We struck up a conversation about the topic of "not giving up hope," which we both had been hearing since we had each been told we were going to go blind. He said something that turned out to be very helpful to me for the next few decades of my life. "Hope for the best, but expect the worst. That way you'll never be disappointed."

If memory serves me correctly, we were both about 12 years old at the time. I've lost track of how many times I've applied that philosophy to make a decision in my life. And yes, it has been a small and cynical part of deciding whether to agree to this implant.

One personal reason I decided on the implant is my age. I'm in my 60's now. Ever since I was young, I've been told that I should never give up hope. "There are new medical advances every day, and you need to stay in touch about them." I was made aware of this implant through a lucky break, and I decided to research it and let the doctors check me out. I needed to stop being cynical about a potential cure and get serious about making a decision.

Besides, if I wait much longer, my age and overall health may end up disqualifying me from being able to take advantage of any future developments.

One thing that tipped me in the direction of agreeing to it is that this artificial retina has an established, proven track record of working for about 350 other blind people worldwide. This isn't only being done in America, it's being done and is available on a global scale. We live in a time of global medical advances and the rest of the world's medical community's opinion on topics and procedures like this implant matters.

But, how do you make the decision?

My point is simple; I know it has worked for at least 350 other blind people. I want anyone reading this to understand that everything I've written here about my decision to do this, is exactly what went through my mind then, and there's more. Some of you may have all of the same experiences that I've had, some not. I can only relate my experience and do not claim that it is the best way, or the right way, to approach a decision like this.

The next part of my decision comes directly from my practical side. I've read what the doctors say about it and have listened to videos produced by the company featuring people who have had one implanted. That's the advertising. I hadn't yet spoken to a blind person who actually has one, either in person or by phone.

For me, when it comes to any product that's supposed to help the blind, I need to speak with a blind person who owns and uses one. So, I asked the company and the doctor to put me in contact with someone who has the implant and has been using it for a few years. They provided me with his contact information along with his permission to talk with him.

I called the gentleman and we had a good talk. When he began statements with: "From one blind guy to another one…," I was instantly comfortable. I felt like I could talk to him and get the truth about what he likes and doesn't like about using ARGUS on a daily basis. I wasn't disappointed. While our lifestyles are different, I did get a wealth of practical information and advice from him. Not all of it may be useful to me, because he lives in a city and I live out in the country, so some experiences don't transfer very well. But, in general, talking to him was a good thing for me to do. It was a good reality check.

Had I been able to speak with many others I'd have done so, but there just aren't that many of "us" out there in my area with this implant. I had to satisfy myself with a sampling of just one.

If you are thinking of having an implant similar to mine, I strongly urge you to talk to as many others as you can about it first. It will help you keep things in perspective. The glare of being able to see something again can be blinding, so I strongly suggest that "you keep it real."

The next phase of how I made my decision is probably unique to me. I stopped talking to others about it (except for my wife of course), turned the computer off and wrestled my past life experiences into an empty room where I locked them up indefinitely.

This decision falls completely outside of anything I've considered doing before, so it was time to just think it all the way through in a quiet and rational way. "Thinking it through" to me means making sure that I understand and accept the risks that go along with agreeing to have a foreign body implanted onto the retina of one of my eyes. I needed to completely process that.

There is a part of the materials that I received that say something like, "The long term effects of retinal stimulation is not known." On one hand, that's understandable. Not many people in the world have this, and they haven't had one in use for a long duration simply because it's so new. I understand that.

What I also understand, and had to intellectually accept is the "…long term effects are not known" part of it. That is the place where each of us who agree to get one, has to knowingly step across the line. In a very real sense, we're stepping from the known into the unknown.

That may sound dramatic to you, but think it through. You can feel the decision get a bit heavier. This is an implanted medical prosthetic. It is not a hearing aid that you can take out of your ear when it bothers you. The implant surgery takes about four hours with two surgeons working on your eye to implant the device correctly. If something goes wrong with it and it has to be removed, or "explanted" as they term it, it will not be a quick and easy process.

And yes, the implant can also "fail" and may need to be replaced, under some circumstances, but at no cost to you.

I am also told that, in some extreme, rare situations, it may require the removal of the entire eye. Hey, that eye may not work very well, but that doesn't mean that I'm "okay" with having it removed.

How long does the implant last?

These implants are designed to last a minimum of five years. How long do they actually last? That's a good question. As far as I know they are so new that nobody really knows exactly how long they last.

I was also told that I'd need to be careful about certain other, non-eye medical procedures in the future. The list is a logical one and makes as much sense as the caution about avoiding sharp blows to the head because that could dislodge the implant.

In spite of all of my research, and having any and all of my questions answered by a very patient surgeon, I had to, in my mind, balance the unknowns and uncertainties of getting this implant against that gold ring of being able to see something again.

I used to be sighted. I know what I'm missing and I want as much of it back as I can get.

I used to wake up in the early hours of the morning rehashing everything I knew about this, in light of all of the unknowns and wondered if I was nuts for even considering having it done.

This mental uncertainty did not end after I decided to go ahead with the implant surgery. I would wake up in the middle of the night, wondering if I had gone nuts.

And the decision?

In my mind, it came down to this — this implant really works, and insurance may very well cover all of its cost. Also, there is this thought that, if I pass this up, will I wonder if I blew my last chance for some eyesight? I'd wonder that for the rest of my life. So, I decided to be an adventurer and said "yes" to doctor Witkin.

What happened next?

Having made the decision, the next phase took matters out of my hands and placed them directly into the hands of the health insurance industry. Sort of a "close your eyes and just jump, everything will be all right" step forward. Either that or I'd be throwing myself off a cliff.

In real world terms, we'd all love to have our health insurance cover everything. The ARGUS II is a "Human Use Device" according to Medicare, so they pay for a very large chunk of it. In addition, I have a supplemental plan that I hoped would pick up the rest. Realistically, my worry at the time was how much wouldn't they cover, and how large a check would we have to end up writing?

I have to offer anyone reading this some advice about insurance. Nothing company specific, but know in advance where your insurance is good. By that I mean, geographically, does the medical facility doing the implant procedure definitely take your insurance? At the time I looked into getting this procedure, I also looked into any alternative medical centers outside of Boston that do it, on the chance that, if Tufts wouldn't take my insurance, who else does this surgery and will they accept my coverage. I knew it was being done in Gainesville, Florida, which isn't far from where my mother lives. She is in very poor health, so we discounted that idea. Then there was Duke medical center in North Carolina, which happens to be very near to where my wife's brother and sister-in-law live. That would be handy to relatives and in a climate where it doesn't snow in the winter. There is such a thing as practicality.

Another issue is what a particular facility will charge for the procedure. The possibility of us being able to stay with family may be an attractive one, but Duke Medical had two other strikes against it right away. First, they absolutely do not accept my supplemental insurance. Second, they bill the procedure out at between $800,000 and $900,000. With only Medicare, I'd be on the hook for a whole lot of that money, if they even accepted me as a patient.

While ARGUS II may be a miracle of modern medical technology, the first thing the "miracle workers" down there want to know is whether or not they're going to be paid in full for the miracle. By the way, for the very same procedure in Boston, the charges would range between $300,000 and $400,000. See what I mean about doing your research? Remember, there is more to this than the actual procedure. There are the mandatory follow up visits to take into consideration. For us, choosing Boston over North Carolina would mean multiple over-night stays in a city that thinks $5 for a cup of coffee is a bargain. Most hotels aren't cheap either, but you can do okay, if you shop around. Just be aware that there are costs associated with this procedure that aren't covered by insurance.

If you read through the online materials about the surgery and follow up appointments, you will read that they suggest you consider temporarily relocating to the area. I'm not sure that's realistic; but then again, look at what your end result can be and what that will mean to you. Please recall that we live in Maine. Maine has no world class medical facilities that can compare to Tufts University Medical Center, the New England Eye Center or Duke University in North Carolina. Having this procedure done in Maine isn't even a consideration. There simply isn't a comparable medical facility within the state.

Getting back to insurance coverage, you may remember that I'd said our insurance would cover the evaluation to see if I am a candidate for the implant. That did not mean they would cover any of the surgical procedure. In fact, in spite of my insurer having paid for the evaluation, I was told that Tufts did not accept my insurance. Yes, they accepted payment from my insurance company for the evaluation, but went on to tell me that they don't accept my insurance for anything else. Same doctor, same place. Remember what I said in Chapter I about insurance companies living in their own world?

This is where a staff member of Second Sight Medical Products came into the picture. In relatively short order, I received a prior authorization notice from my health insurer stating that they'd cover the procedure for a 30-day time period. That may sound pretty good, but it's completely unrealistic. Tufts resubmitted a new request for authorization, and I received a second one, which again authorized the procedure for another 30-day window. The problem is this; scheduling a procedure like this one in that short time period isn't realistic when you consider that you're trying to get a specialized surgical team together in the same place at the same time. Finally, after multiple efforts by the gentleman from Second Sight, the insurer issued another prior authorization letter that covered a one year time frame. At last, everyone, including me, could relax.

Did this mean that I knew, dollar for dollar, to the penny, how much it would cost and exactly what my share of it would be? No. Not at all. But it was clear that I was "covered."

With the date for implant surgery set for April 19, 2019 I settled down to await the day. Inside I was very roiled up. This is a very big deal for me. And, just to make sure you understand that mistakes can, and will jump up and bite you at any time, One day before the surgery and again one month after my implant surgery, I received a call from Tufts Medical Center billing department notifying me that they do not accept my insurance for the surgery. After my heart and stomach returned to their assigned places, the Prior Authorization letter was retrieved each time from our files and faxed down to Tufts, Second Sight Medical Products and my surgeon. By the next morning the "misunderstanding" had been cleared up. This is just how things work when you're dealing with an insurance company for something other than a mundane medical issue. When "shit happens," rolling with a punch like that one requires some control over your vulgarity settings.

Chapter 3: Implant Surgery

"General anesthesia is so weird. You go to sleep in one room, then wake up four hours later in a totally different room. Just like in college."

- Ross Shafer

After I'd decided to have the implant surgery, Second Sight Medical Products asked me if I'd consider letting them do an educational and marketing video of my adventure through the entire process. Seeing no harm in it, I said sure, why not? This resulted in a marketing company person with a cameraman and production man from Second Sight Medical products coming to my house for "Phase 1." They came to our home two days before the surgery to film me doing various things around the house "without the ARGUS II implant."

This was an interesting experience for us. After five hours of them filming me in the house and outside doing daily tasks, they departed. We'd be seeing them again in two days at the hospital. To me, this was fascinating. I signed releases agreeing to let them film me. Then they had to go through the PR department at the hospital, so they could interview the doctor and shoot video of me there, as well.

We'd traveled to Boston the day before surgery and spent the night at the Parker House. I cannot say enough good about the staff there. They knew I was in Boston for some rather unique surgery and really went the extra mile to make me comfortable and make sure that, if I needed anything, they'd "be right there." They were certainly true to their word, too.

The morning of surgery, I arrived at the Tufts pre-op department at 6:30 a.m. with no breakfast or even coffee, as is the norm for a surgical procedure. The marketing crew filmed an interview with the doctor, then filmed him explaining things to me for the sake of whoever would be watching the video in the future. Then it was down to medical business. I was already tired. I'd been unable to get any sleep the night before, in anticipation of the surgery.

The first thing to happen was that an anesthesiologist laid a comforting hand on my shoulder and told me that I'd be under a local anesthetic for the procedure, "just like for Cataract surgery." My head snapped around to look in the direction of his voice (remember, I'm blind) and said: "Oh no. That's wrong. I was told I'd be under a general anesthetic. This isn't right." He patted my shoulder reassuringly and said in his most calming voice: "It'll be all right sir, nothing to worry about."

I said, "There's plenty to worry about. This is wrong." Then I said I wanted to see the doctor before we went any farther. The doctor came into the room asking what was going on. Advised what the situation was, he told the anesthesiologist that it was indeed a general anesthetic. Well, Tufts is a teaching hospital.

Next, they briefed my wife on how she could track my "progress" by looking at airport-type monitors to find a special number that had been assigned to me. The color of the number signifies how far along I am at any given time. So, after a kiss on the cheek from my wife, I was given a pre-anesthetic drip in my IV. I closed my eyes and tried to relax. That is the last thing I remembered until I was awakened by someone insistently pushing a plastic straw at my mouth entreating me to "drink something." Before you rush to any adverse conclusions, this was my wife trying to get me to take a drink of ginger ale. That was four hours later. The operation was done. I recall that the ginger ale tasted remarkably sweet. I think I also ate some sort of cookie at the insistence of the recovery nurse. I really was "out of it."

What should I expect post-surgery?

The last time I'd been under a general anesthetic was back in junior high school when my appendix was removed. Other than taking aspirin for a headache and some meds for cholesterol and blood pressure, I don't take any strong medications. That recovery room time is downright foggy for me. As I found out after receiving a copy of the hospital billing statement, the list of drugs I'd been given was two pages long. No darn wonder I was so spacey. I do recall saying, more than once, "I signed up for this?" I felt as if I'd been knocked out by a prize fighter who'd punched me in the eye.

While this immediate post-surgical feeling is only to be expected after two surgeons spend four hours working on my eye, the after effects of a general anesthetic was entirely unexpected. I was totally unprepared for the wooziness of the drugs and dehydration caused by the breathing tube. Remember that this is an outpatient procedure, meaning that after some recovery time, you go home or back to your hotel room, as the case may be. Perhaps my overall woozy reaction was because I'm so unaccustomed to any kind of strong prescription medications. To put this into perspective, I've never needed help putting my pants on before.

When the nurse poured me into a wheelchair, I asked her where I was going next. The nurse told me I was going back to the hotel. This surprised me because I could barely stand up.

My wife managed to shoe horn me into an UBER car for the trip back to the Parker House.

Once there, the doorman took one look at me and hustled to get the regular door open for me, since the revolving door was completely beyond my ability at that time. I did toy with the idea of simply flying up to our room to meet my wife when she'd gone up in the elevator, though. I felt like I could do that, easily. Were it not for my wife holding me upright, however, I never would have made it up the six steps into the hotel lobby.

I'll give anyone going through any surgical procedure similar to this one a word of advice. If the hospital staff offers you prescription pain killers, take them. I recall little about the remainder of that day. I wasn't hungry, but intellectually knew that I needed to put food in my stomach because I hadn't eaten since the previous day. My wife ordered room service, a darn good idea since I was incapable of navigating down to the restaurant. She ordered a sandwich for me, another excellent idea, considering how incapable I was of using complicated equipment like a knife, fork or spoon. I could only eat half of a sandwich, but owing to the anesthetic-generated dehydration, I couldn't seem to get enough water to drink.

I made darn sure that I took one of those pain pills once every four hours, though. I needed them. Any sleep I got that night, even having taken one of those pain pills, was at best, fitful. By the next morning, I really didn't feel the need for a pain killer. A dose of Tylenol took care of what was, by that time, only mild discomfort. One aftereffect of all of the medications I'd been given the previous day, was that my taste buds were completely shot. The Parker House' restaurant is known for wonderful food. The only thing I could taste was the bacon that came with the scrambled eggs I ordered for breakfast. I couldn't taste my coffee until I was halfway through my second cup.

That morning, we had to be at the doctor's office for the obligatory morning follow up. After I was told that all was well, we were on our way back to Maine in short order. Although I felt better, I remained in a stupor all of that day. After we got home, my stepson asked if I was actually going to go to bed early. You bet. I was in bed by 8 o'clock. Speaking strictly for myself, there is a lot of truth in the old saying that you always sleep better in your own bed.

Since my surgery, I've spoken with two other people who have had an ARGUS II implant. One person said he was just fine the next day, more or less similar to my experience. Another gentleman reported that he was miserable for two or three days afterwards.

The point you should take away from my experience is that no two people are going to have the same reaction to what is definitely serious surgery. However, each of us came out of it just fine.

Chapter 4: What turns me on?

"He that is strucken blind cannot forget the precious treasure of his eyesight lost."

- William Shakespeare

Obsolete already?

Between April 19, 2019 when the ARGUS II artificial Retina was implanted in my right eye, and May 31, 2019 when I was "activated" (as the technicians refer to it), I was quite restless. I wanted to get on with it and see what I was actually going to be able to "see."

The very first thing I learned at my activation appointment was that, as of September, 2019, Second Sight Medical Products will discontinue the implantation of ARGUS II artificial retinas in patients. They have decided to focus exclusively on the development of their new implant the "Orion" which is pretty much the same thing as an ARGUS II implant chip. Orion will go directly onto the visual cortex of the patient's Brain. Of course, this method bypasses the optic nerve altogether and significantly increases the patient eligibility population. With an "Orion" being implanted directly onto the visual cortex, people whose optic nerve has been damaged or destroyed can now benefit from this wonderful medical technology. At the time of this writing, there are six test subjects who are implanted with the Orion and I understand that the results thus far are quite promising.

So far, the Orion visual cortex implant has not been approved for use by the FDA. The ARGUS II retinal implant that I have is approved. So, any potential Orion candidates will need to wait a while yet.

Being greeted with this news on the very day my implant was to be "activated" told me that I'd gone from having the latest state-of-the-art retinal medical prosthetic implanted on my retina, to being obsolete. Well, that change had taken less than three weeks from the date of my surgery, hadn't it? If needed, this is more proof that technology sure changes fast. My very first question to the doctor was how long Second Sight Medical Products would continue to support the ARGUS II patient population. Apparently, the answer is "for life." Or, at least for the life of the ARGUS II implant. This question would come back to bite me in less than ten months.

The new generation of recipients receiving an Orion on their visual cortex will get the same kind of glasses and visual processing unit that those of us with an ARGUS II implant use. With the same kind of equipment being used by both types of implant, the ongoing support is easily accomplished.

Once that conversation was done, it was down to business. Once again, the marketing company for Second Sight Medical Products was on hand to video my activation. Thankfully, that day we were all in Boston at the surgeon's office, instead of a more formal setting. There were more people in attendance than I'd anticipated. There was the marketing person and her cameraman. There was also my doctor and two people from Second Sight Medical Products. These two women are what Second Sight calls "Artificial Vision Rehabilitation Managers." One flew in to Boston from the Chicago area and the other had recently relocated back to the Boston area from a job she'd had in Florida.

For those of you who are blind and may be considering an implant like mine, I'll clarify something for you. Second Sight Medical Products may call them Artificial Vision Rehabilitation Managers, but don't interpret that to mean that I was assigned two Vocational Rehabilitation Counselor types. These managers are highly specialized technicians with a very unique skill that only a few people have nationwide. For example, the woman who'd flown in from Chicago is the person who "programmed me." This means I was hooked up to her computer so that she could activate each of the 60 electrodes on the implant, one at a time, through the visual processing unit I'd be wearing, and each one at a varying power. I was handed a video game controller with one button on it that was active, and when I "saw" a flash of light, I was to push the button.

As you may guess, this was a time-consuming process. Some of those flashes were bright and very definite, while some were faint and barely there. After four hours of this process, my personal "program" was ready and saved in my personal Visual Processing Unit (that's VPU in Second Sight Medical Products lingo) that I would wear whenever I had ARGUS turned on. Presto, I was then "activated" and I was "turned on."

The only person I wanted with me right then was my wife and I said so. The doctor asked me if I'd seen any movement in the room go by in front of me, and when I said yes, I'd seen a hint of movement, he told me I'd just seen my wife coming over to me. For the first time in decades, I was "seeing" my wife. What I wanted to do was jump up and throw my arms around her, but I couldn't do that, because the room was quite literally overstuffed with people, not to mention how undignified it would have been.

I have a very close relationship with my step son Kevin, who I'd asked to be there for my activation. He is the sole reason we have some cell phone video of the big moment. He is 6 ft. 7 inches tall and had no trouble at all taking video of the big moment over everybody's head with his cell phone camera. The cameraman who works for the Marketing company had to stand on a chair to try and get the same type of camera angle. That was a priceless moment to capture.

What can I expect to see now?

Of course, the real big question is "what can I see now?" This is where things become difficult. The kind of flashing lights I actually see, within the context of any given situation, almost defy description. It is so very different from anything I've ever experienced before that I find myself struggling for words. That first day was very tiring. Four hours to get my "program" set up, followed by a short interview with the marketing folks and then a late lunch. I was told to leave the ARGUS off for the rest of the day and for the following day to give my ARGUS II eye a rest. Then we drove back to Maine. I was permitted to wear it for two hours one day later, then leave it off for the day following that.

The day after the second "off" day was to be the start of the real training. In fact, the cameraman, marketing company owner and both of the Vision Rehabilitation Managers were going to be at my house for five hours a day, for the following two days. I learned not to wear ARGUS for more than an hour at a time to start. It is possible to burn your retina out using an ARGUS II. This means that there is such a thing as "too much of a good thing." The first day, we used ARGUS around my home, indoors and out. I learned the four different modes and how to use them.

When the VPU first "comes up" and flashing lights appear in my eye, I am in the basic mode; it always "boots up" in this mode. I can then shift from the basic mode into mode #2, a more intense, enhanced version of the basic mode, that gives me more, brighter flashing lights. The best description I can give this is that it translates into me having a bit more definition to whatever I'm "detecting" with the camera.

Then there is "edge detection." This better defines "edges" for me, such as doorways, rooftops, fences outdoors, and anything else having a well-defined hard edge to it. Next, there is "reverse polarity." And yes, this means what you think it does. Light becomes dark and dark becomes light. You can activate that mode and use the other 3 modes within reverse polarity mode. This translates into a learning curve of a type that I've never experienced before.

Perhaps this explains why it is so difficult to describe what I "see" now. Add to all of the foregoing, that ARGUS has no depth perception capability to its processed images, and that my visual field is 20% of what I had back when I could still see. The challenges involved with using artificial vision should start taking shape for you, and give you an idea why having an Artificial Vision Rehab Manager available to you is so important.

Remember, using this is a bit like looking through a periscope. I have no peripheral vision, so if I want to see something off to my right, I have to turn my head until the camera mounted on my glasses detects whatever is there.

Within the first ten or fifteen minutes of using ARGUS II out in the real world, I started using the various modes individually or in conjunction with one another to better detect, or detect and then try to define objects that I'm detecting. And, before I go any farther with a description of what I'm seeing (detecting) with my ARGUS II, I need to tell you about something that I've experienced while using my new artificial vision.

For the first time in decades, my right eye's optic nerve is sending visual signals to my brain. My brain, in particular the visual cortex, hasn't experienced any "motion related visual input" for a very long time. So now, it is not only receiving input in the form of flashing lights that the rest of my brain is trying to interpret, it's also detecting "motion" again. That means, if I move my head too quickly, or in an up and down motion, to look at something above me, I get a bit seasick. I can't speak for others who use ARGUS II, so I don't know if they experience the same thing. I can only report what I'm experiencing.

My point in relating this, is so that anyone considering an implant like this will know what he or she may find they need to adjust to when they are "activated" and begin to see things again.

It's logical, common sense to me. If you haven't seen anything in thirty or forty years, your brain has some adjusting to do and it's going to take some time. I also learned that, if my implanted eye feels tired, I need to turn ARGUS off for a while.

The second day of training with ARGUS II was out in the community. This day's training was broken down into two trips. The first trip was to a rather unique place here in Augusta, Maine. You can find it online as "Old Fort Western." It was built in 1754 as a sort of supply depot for other military forts up and down the Kennebec River. All of the forts are cited on the river. Well those that still survive are.

Using edge detection to locate the palisades and doorways was a unique exercise. Owing to my wife's status as a trustee at the Fort, we were permitted inside on a day when it would normally be closed to visitors. Detecting the stairs to get to the upper levels of a blockhouse with cannon mounted in it, taught me how important it is to have decent lighting if I wanted to be able to accurately detect things. It's very easy to forget that I'm "seeing" through a camera, not seeing a camera image on a screen of some sort. I can also tell you that an ARGUS II is very poorly suited to accurately aiming 18th century artillery.

After a break for lunch, the Vision Rehabilitation Managers and I traveled in town to a large local grocery store for some practical, real world exposure. This environment took me from a poorly lit Fortress built in 1754 into a modern, very well illuminated grocery store. You couldn't have found a more alternate environment for me to visit that day. It was almost an overload for me. ARGUS II was detecting a variable clutter of flashing light things all around me with none of it having any depth perception to it. This is also where I learned that I couldn't detect anything on the other side of a pane of glass. For example, trying to see something through the glass door of a milk cooler completely defeated me. By the time that days training was done I'd learned a great deal about how much more I had to learn about using artificial eyesight.

A day or two later, my wife and I went to a popular walking trail that runs along the river. There is a traffic bridge that runs across the trail, and is elevated by roughly forty feet. In an effort to see what the bridge looks like with ARGUS using "edge detection" mode, and to see if I could detect the motion of cars driving on it, I looked up at it. I detected the span of the bridge with no trouble, but was at the wrong angle to be able to detect any movement on it. When I looked "up" at it, my surroundings slid "down" out of the ARGUS II camera view, then slid back "up" into it when I brought my head back down. That's when the seasickness hit me. The visual stimulus of the up and down movement to my brain awakened a long dormant vision-triggered vertigo. Using ARGUS II is not going to be a quick adjustment.

Before anyone reading this interprets some of what I say as frustration or disappointment, let me clarify things. What I now have with an artificial retina is 100% more than I had before it was activated. I went into this knowing I wasn't getting my eyesight back. I knew I was going to get artificial vision that I had to learn how to use. Learning to use something this alien is a challenge. I intend to push this device as far as I can to get as much as I can out of it without burning out my retina.

After that second day of training, I was "on my own" to use ARGUS II in my daily living. Since then, I've also learned a few things that are completely unexpected. You may recall me saying that my brain is trying to adapt to receiving visual input again, both in interpreting flashing lights and in experiencing motion. For the first time in years, I've noticed some visual phenomenon that I find quite curious. Again, it's very difficult to describe. To begin with, and for the benefit of those reading this who are not blind, let me explain things in a way that you will understand. The term "blind" does not mean all black. Blindness has varying degrees of visual acuity. There is "legal blindness" and a wide range of "partial sightedness" which is all a part of what is defined as being "blind."

To be eligible for an ARGUS II artificial retina, I had to have been able to see once, have a functional optic nerve and be generally healthy enough to go through the surgery. That's a thumbnail outline, but was the essential requirements. Another requirement is to be blind enough to actually need the addition of artificial eyesight. Again, I certainly qualified there. So, before getting this implant could I see anything at all? The answer to that is that it depended on the day. I have, or had, very small slivers of normal eyesight in the very corner of each eye. That isn't much.

The rest of my visual field, better stated as my "nonvisual field," was either pitch black, solid white, as if I were in a thick fog bank with a bright white light being shined on it, or black with tiny white dots in it, much the same as what you used to see on a very old TV show called "Star Trek" when looking at the "star field," often shown on the bridge of the space ship for the show. Sometimes the dots cluster into a group, then fade away.

When I asked my eye doctors what caused this and what it meant in a medical sense, I never received an answer. They just didn't know what I was experiencing. As you keep all of this in mind, the following are the "nonvisual" field phenomenon I began to experience after the ARGUS II implant was activated. Remember, the implant doesn't receive "camera pictures" from the VPU. It receives electric impulses representing the camera images. These are the flashing lights that my retina "sees" and what I experience.

For one thing, after implant surgery I could "see" a light-colored cloud in the implanted eye's nonvisual field corresponding to the implant's location. I found that interesting because this appeared after my implant surgery and more than a month before activation. "Activation" is after my VPU was programmed and it was sending the electrical impulses through the implant's electrodes into the retina. That's what Second Sight Medical Products means when they refer to "stimulation." The flashing lights I keep referring to is the result of that stimulation.

Within a week or so of using the ARGUS II for the recommended two hours a day, I began to experience new things in my nonvisual field when the ARGUS II was not on. One thing was a return of blue or purple "blobs" that swirl about the field for a few seconds. If you close your eyes and rub them, most people will experience these swirling blobs. I haven't seen them for decades but they returned in the implanted eye, and I was thrilled to "see" them again after they've been gone for so many years. You'll laugh, but it was a bit like seeing an old friend after years of absence.

Another new experience is individual flashes of light in the implanted eye, and I'd see them outside of the implant's location. Sometimes these tiny individual flashing lights would fade, and sometimes they'd remain and group into a cluster of lights. Other times, I would see a cloud of light, sometimes at the implant's location, sometimes not, that would grow in intensity until it was so bright that it became downright annoying. Whether my eyes were open or closed had no effect on them.

As time progressed, the swirls of purple or blue blobs began to appear in my left eye as well, as did the bright cloud of light. That was fascinating to me. My left eye isn't connected to the right one where the implant is located. My guess about those individual flashes of light is that the "stimulation" of my optic nerve is causing some stimulation bleed over. Perhaps the electrical impulses stimulated nearby parts of the optic nerve?

Another thing I began to notice, is that the tiny sliver of natural vision left to me in my left eye began to brighten. This is hard to describe, but that sliver of eyesight is brighter and perhaps a bit sharper. However, that bit of eyesight is so small that it's hard to be definite about this. But I assure you something is happening in my left eye and I believe it's an improvement in clarity. There is no expansion in the size of that sliver of eyesight, though.

I begin to see what the Second Sight Medical Products ARGUS II print materials mean when they state that "the long-term effects of retinal stimulation are not known." To be clear, I have no idea if any other ARGUS II users experience these same types of phenomenon. Remember, there are only about 350 or so of us world-wide with an ARGUS II implant and there will be no more of "us" after September of 2019. Will any of the new "Orion" implant users experience similar phenomenon? Who knows? Only the men and women who get one will know.

I also need to bring another, slightly less critical thing to light here. That's communication.

For those of you who are blind, or otherwise visually impaired, you will understand this much better than those reading this who are sighted. It is a significant challenge to articulate or write an accurate description of something this new and alien to those who are not, and probably never will be, experiencing it. Those of us who are blind have the challenge of describing something accurately to the rest of you and it isn't easy.

Chapter 5: Pushing The Envelope

"The voyage of discovery is not in seeking new landscapes but in having new eyes."

- Marcel Proust: "The Captive"

This takes time and concentration.Once all of the programming and trainings concluded, I was "on my own." Well, on my own, insofar as being cleared to use the ARGUS II for two hours a day, all by myself. I also knew that, if I had any problems or questions, I could ask the surgeon who did the implant or one of his "team" in Boston. I can also ask questions or voice any concerns I may have to either of the two Artificial Vision Rehabilitation Managers who work for Second Sight Medical Products, or I could contact Second Sight directly.

Now on my own, I'd told the doctors as well as the Second Sight people a similar thing. I intend to push the ARGUS II to its limits. I want to see as much as I can with it. I was reminded to use ARGUS "within limits" so that I didn't "burn out" my retina, as at least one person with it has reportedly done. With that warning in mind, I've gotten on with my life, with the added benefit of artificial eyesight.

Believe me when I say that I have been putting this artificial retina through its paces. I go to the grocery store with my wife. I go to furniture stores, Home Depot stores, Lumber yards, construction supply stores, local coffee shops, doctor's offices, my cardiologist's office, Walmart and just about any other place we need to go. My poor long-suffering wife has been pure gold throughout all of this. If I see something that I can't identify, I'll ask her what it is or how far away it is. She's always patient with my questions. Also, she won't hesitate to get behind me and "sight" over my shoulder to figure out what I'm looking at so she can give me an accurate answer.

One day I asked her if we could get some lunch and eat it down at the river that runs through downtown Augusta, so that I could try to see water and any boat traffic moving on it. I've always loved the water and boats. She walked me down to the river's edge and asked me if I could see the mother duck and her eight ducklings in the water right in front of us. Sadly, I could not. Amazingly enough, however, I was able to detect the roof line and corners of a building that was on the far side of the river from us. When I told her I could detect a taller "something" to the right of that building, she moved behind me to sight over my shoulder to see which structure I was talking about. I was looking at the bank building which is several stories taller than the first building that stands right next to it.

As we figured out, via the internet, after returning home, the river is 900 feet wide at the place we were standing, and the "tall" building I'd seen is 110 feet tall. To put this into perspective, I could not see the ducks on the water right in front of us, but I could see buildings that are 900 feet away. I never thought I'd ever be able to experience that kind of vision ever again. I think I know why I could see the buildings across the river and not the family of ducks.

The family of ducks was a dark color and the water was likewise a dark color. No matter which mode on the ARGUS VPU I tried, I could not detect them at all. On the other hand, the buildings I detected were on the far side of an unobstructed view with some contrast. Both buildings are large angular structures, and the sun was not shining on the water to create any glare which could inhibit the camera picking them up. In addition to the buildings, I was also able to detect the bridge spanning the water, just upriver from where we were standing. I could not detect any movement of the cars driving across the bridge, though.

The lack of any depth perception inherent in using this device definitely takes getting used to. As thrilled as I was to know that I was seeing buildings and a span of bridge, I was a bit frustrated when it came to my efforts to see a picnic table under a nearby tree on the river bank. There were other trees and bushes growing in the same area. So, things under the tree may have been closer to me than those buildings had been, but it was in a cluttered environment, compared to my unobstructed view across the river.

When you have no depth perception, foreground and background tends to meld together and you end up with "clutter" that your brain has to try and sort through. Add to all of this, that I'm trying to train my brain to accept that its field of vision is only 20% of normal, which is the equivalent of looking through a hole the size of a 3x5 card held out at arm's length. That's a lot for the human brain to put into perspective, after not seeing anything for decades. In many ways, using artificial eyesight in a useful way begins with the "standard" of object or obstruction detection, not object or obstruction identification. Remember, I'm seeing flashing lights that I have to learn to interpret. Like I said, getting used to this type of vision takes time and concentration.

Then there is the issue of dealing with people who see you wearing a pair of glasses that are wired to something you wear on your belt. For example, there is our trip to the shop where my wife gets her hair cut. The glasses I wear with the tiny camera mounted on them does not look like your average pair of sunglasses. There's a wireless coil that is mounted on the side of it which is what transmits the signals to the implant. My point is that, once people realize the glasses aren't "normal" glasses, I end up having to explain what I'm wearing to them. This doesn't bother me. In fact, I'm amazed how many people express genuine curiosity in artificial eyesight.

Another part of using an artificial retina and its equipment that I need to get used to, is using the VPU and being aware of the life of its batteries. I was issued three batteries to go with it, and each battery is good for two or three hours, depending on how you use it. Since I tend to use the ARGUS in as many different environments as possible and in as many different modes as possible, I tend to drain each battery quickly. I am guessing when I say this, because I've never used things to the point where the low battery alert sounds. As I've said, I'm only using this for two hours a day, so far.

Another aspect of adapting to using artificial vision is matching the actual capability of the ARGUS with what I'd like it to do for me. Let me explain that statement. In technological cost alone, I have more than $250,000 in my eye and in external equipment (such as it is). One aspect of ARGUS I need to work better with, is that lack of depth perception I mentioned above. Remember that I'd detected two buildings on the far side of the river when my wife and I were eating lunch there. I had absolutely no idea how far away those buildings were until she told me. So, the ability to see is offset by the need to exercise extreme caution while using it for mobility.

In practical terms, it tempers how much I can trust the device to keep me safe while using it to walk around. I need to understand how to use the visual signals I receive from it and the safest way to use them in conjunction with my white cane. In that sense, ARGUS II is an orientation and mobility supplement. ARGUS II artificial vision means no depth perception and a small visual field. These limitations are only two examples of learning how to use this kind of vision.

Using ARGUS out in the world has its amusing moments. Recently my wife and I had to run some errands in the car, and we stopped to get some gas. While my wife pumped the gas, I wanted to see how well I could detect hand movement with the ARGUS camera while holding up two fingers. I held up two fingers in the small sliver of natural vision that remains to me in the corner of my left eye. I tried the two fingers in front of the ARGUS camera, then changed to comparing the image of my entire hand in front of the ARGUS camera and then in the sliver of natural vision. A minute later my wife got back in the car and said, "Sometimes I forget that you aren't fully aware of your surroundings. While you were testing something with your hand and the ARGUS, two women in a car who were about to leave the gas station stopped and looked at you because they thought you were waving at them."

"Did you say something to them?" I asked.

"No," she replied. "After a minute or two, they seemed to decide that you're nuts and just drove away." Sometimes I manage to embarrass myself like that.

Another new aspect of artificial vision that must be learned is the practical reality of using a camera that is the "feed" for my new vision. If you think about that for a minute, the effective use of this device means that a blind man needs to learn how to interpret a digitized camera image that has been processed into flashing lights by a small computer. Then, he must accurately interpret them into useful information that can be safely acted upon in the real world.

Like I said before, I'm not seeing a camera's picture, I'm seeing a camera's image of flashing lights, as processed by a visual processing unit.

During a recent trip to the grocery store, my wife had to stop me from walking into a vertical support column in one of the aisles. As it turns out, that column is a dull grey color with no reflective properties to it at all. Since that is the visual reality, I was faced with something that is, in the "eye" of my camera processed image, so well camouflaged that I was not able to detect it. That column simply blended into the background clutter. If you recall the duck family I was unable to detect at the river, this is the same situation in a different setting. As my wife pointed out with her usual flawless accuracy, when I use the ARGUS, I'm not using my cane the way I usually do. That isn't just an observation, it's pointing out a safety risk I'm taking. She's right. I have been relying on the ARGUS imagery in place of the much safer, direct tactile feedback from my cane. I should be using my cane to verify what I'm detecting with ARGUS, and confirm that there are no other obstacles in my path. Simply stated, I'm trusting ARGUS too much. This is another aspect of ARGUS use that takes work and adaptation. Instinct and training with some newly developed discipline is very necessary here.

Keeping all this in perspective.

To try and keep all of this in perspective, I urge anyone considering an ARGUS or Orion to take to heart the qualifiers you will find repeated in written materials for this kind of technology. "Everyone has different outcomes." And "the long-term effects of this type of stimulation are not known."

Some problems that I have written about here will be either nonexistent or much less intense for someone else. My advice is to keep your expectations realistic and flexible.

There is one final point I wish to make in this chapter: for those of you who are not blind or visually impaired, there is a big issue of trust in using technology like this. In daily use of my cane, I have learned to trust what I'm feeling through its handle. If I'm letting someone guide me, known as a "sighted guide," I'm placing my physical safety in the hands, pardon me, eyes and judgement of that person. That is a large amount of trust and faith I'm putting into him or her. There are people I will not accept sighted guidance from, simply because they just don't pay attention.

Applying that type of trust to the ARGUS II is something I have not yet done. I am told that there is a software and camera upgrade on the way for us ARGUS users. The camera is of much better quality, and the VPU software has facial recognition capacity and even thermal imaging added to it, as well. This upgrade has been "on its way" since 2016 and has not yet been approved by the FDA. When it is released, and assuming it lives up to its potential, the upgrade may very well enhance my trustworthiness of the equipment to a point better than what I have now.

Nothing like waiting for a Federal agency to give its approval for something.

Chapter 6: Side Effects

"There are things known and there are things unknown, and in between are the doors of perception."

- Aldous Huxley

Are there side effects?Since Second Sight Medical Products is up front about not knowing what the long-term effects of ARGUS II stimulation will be, I thought I'd add in a chapter on what I view as being side effects. If life teaches you anything, it's that there are potential side effects to everything from taking aspirin for a headache to failing to stick to a diet. That's just the way life is.

Back in Chapter 4, I mentioned feeling a bit seasick because I'd "looked up" to see a bridge that was above me. I attributed that feeling to my brain and optic nerves reacting to "seeing" movement for the first time in years. I still believe that. However, the vertigo that goes along with that seasickness stuck with me for quite some time, until my brain began adjusting to it. I consider this a short-term side effect.